They Paved Our Way

1731-1806

Benjamin Banneker, the son of Robert and Mary Bannaky was born in 1731. His grandfather was a slave from Africa and his grandmother, an indentured servant from England. His grandfather was known as Banna Ka, then later as Bannaky, his grandmother as Molly Walsh. His grandmother was a maid in England who had been sent to Maryland as an indentured servant. When she finished her seven years of bondage, she bought a farm along with two slaves to help her take care of it. Walsh freed both slaves and married one, Bannaky. They had several children, among them a daughter named Mary. When Mary Bannaky grew up, she bought a slave named Robert, married him and had several children, including Benjamin.

Benjamin Banneker grew up on the family farm. Around town it was known as "Bannaky Springs" due to the fresh water springs on the land. Bannaky used ditches and little dams to control the water from the springs for irrigation. His work was so reliable that the Bannaky's crops flourished even in dry spells. The family of free blacks raised good tobacco crops all the time.

Molly, Banneker's grandmother, taught him and his brothers to read, using her Bible as a lesson book. There was no school in the valley for the boys to attend. Then one summer, a Quaker school teacher came to live in the valley. He set up a school for boys. Benjamin Bannaky attended this school. The schoolmaster changed the spelling of his name to Banneker. At school he learned to write and do simple arithmetic.

When Banneker was twenty-one, a remarkable thing happened: he saw a patent watch. The watch belonged to a man named Josef Levi. Banneker was absolutely fascinated with the watch. He had never seen anything like it. Levi gave Banneker his watch. This was to change his life. Banneker took the watch apart to see how it worked. He carved similar watch pieces out of wood and made a clock of his own; the first striking clock to be made completely in America. Banneker's clock was so precise it struck every hour, on the hour, for forty years. His work on the clock led him to repair watches, clocks and sundials. Banneker even helped Joseph Ellicott to build a complex clock. Banneker became close friends with the Ellicott brothers. They lent him books on astronomy and mathematics as well as instruments for observing the stars. Banneker taught himself astronomy and advanced mathematics.

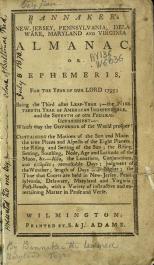

A reproduction of the cover of an original Banneker Almanac Banneker's parents died, leaving him the farm since his two sisters had married and moved away. Banneker built a "work cabin" with a skylight to study the stars and make calculations. Working largely alone, with few visitors, he compiled results which he published in his Almanac.

Around this time, Major Andrew Ellicott, George Ellicott's cousin, asked Banneker to help him survey the "Federal Territory". Banneker and Ellicott worked closely with Pierre L'Enfant who was the architect in charge of planning Washington D.C. L'Enfant was suddenly dismissed from the project, due to his temper. When he left, he took the plans with him. Banneker recreated the plans from memory, saving the U.S. government the effort and expense of having someone else design the capital.

Although Banneker studied and recorded his results until he died, he stopped publishing his Almanac due to poor sales. Banneker died on Sunday, October 26, 1806. For years he has been referred to as "the first Negro Man of Science".

Bessie Coleman trained in Paris to become first female African American pilot

In 1920, Bessie Coleman (1892-1926) became the first African-American woman to earn a pilot’s license, after traveling to Europe to attend flight school.

Born in Atlanta, Texas, Coleman moved to Chicago in 1915, and here she discovered her passion for aviation. However, as a black woman she wasn’t allowed to train as an airplane pilot in the United States.

Robert Abbot, publisher for the African-American newspaper the Chicago Defender, urged Coleman to learn French and enroll in France’s Caudron School of Aviation.

Coleman received her international pilot’s license and toured the U.S. as a barnstormer, with the Chicago Defender as her sponsor. Coleman, who gave lectures and flight lessons, became known as “Queen Bess” and “the world’s greatest woman flyer” as her celebrity grew.

Her first Chicago area exhibition was Oct. 15, 1922, at the Checkerboard Field, in what is now Miller Meadow Forest Preserve in Maywood. More than 2,000 people attended.

She died in a plane crash in Florida in 1926 and is buried in Lincoln Cemetery, at Kedzie and 123rd in Alsip.

Sources: Encyclopedia of Chicago and Smithsonian Institution Archives

Bessie Coleman Trained in Paris to Become First Female African American Pilot

1892 - 1926

Ernest Everett Just

(1883-1941)

Originally from Charleston, South Carolina, Just attended Dartmouth College and the University of Chicago, where he earned a Ph.D. in zoology in 1916. Just's work on cell biology took him to marine laboratories in the U.S. and Europe and led him to publish more than 50 papers.

Benjamin Bradley

(1830?-?)

A slave, Bradley was employed at a printing office and later at the Annapolis Naval Academy, where he helped set up scientific experiments. In the 1840s he developed a steam engine for a war ship. Unable to patent his work, he sold it and with the proceeds purchased his freedom.

Lewis Latimer

(1848–1928)

One excellent example of the African American achievers in science is Lewis Latimer. His father, George, was as ex-slave who escaped slavery in 1831 and fled to Boston. Eleven years later in 1842, his former owner appeared and tried to take him back into slavery but many members of the Boston community rallied on his behalf and raised the $400 necessary to buy his freedom. Black abolitionists and Whites, such as Lloyd Garrison raised the moral consciousness of the public.

The son, Lewis, settled in Chelsea near Boston but when the Civil War broke out he joined the navy. His brother fought in the Army. After the war, Lewis Latimer became a draftsman and handled the telephone patent for Alexander Graham Bell. His first patent was granted in 1873 when he invented a water closet for railroad cars. In 1880 he worked for the inventor and industrialist Hiram Maxim in the U.S. Electric Lighting Company and the following year he received patents for an improved carbon filament which eventually aided Thomas Edison in his work on the incandescent light bulb. Latimer joined Edison and used his expertise to write one of the first books on lighting cities in America and England. He also helped Edison win several crucial legal battles over patents. Later he became a founding member of the Edison Pioneers.

Dr. Charles Richard Drew

(1904-1950)

Born in Washington, D.C., Drew earned advanced degrees in medicine and surgery from McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, in 1933 and from Columbia University in 1940. He is particularly noted for his research in blood plasma and for setting up the first blood bank.

Patricia Bath

(1942-)

Born in Harlem, New York, Bath holds a bachelor's degree from Hunter College and an M.D. from Howard University. She is a co-founder of the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness. Bath is best known for her invention of the Laserphaco Probe for the treatment of cataracts.

Thomas L. Jennings

(1791-1859)

A tailor in New York City, Jennings is credited with being the first African American to hold a U.S. patent. The patent, which was issued in 1821, was for a dry-cleaning process.

Mark Dean

(1957-)

Dean was born in Jefferson City, Tennessee, and holds a bachelor's degree from the University of Tennessee, a master's degree from Florida Atlantic University, and a Ph.D. from Stanford University. He led the team of IBM scientists that developed the ISA bus—a device that enabled computer components to communicate with each other rapidly, which made personal computers fast and efficient for the first time. Dean also led the design team responsible for creating the first one-gigahertz computer processor chip. He was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1997.

Garrett Augustus Morgan

(1877-1963)

Born in Kentucky, Morgan invented a gas mask (patented 1914) that was used to protect soldiers from chlorine fumes during World War I. Morgan also received a patent (1923) for a traffic signal that featured automated STOP and GO signs. Morgan's invention was later replaced by traffic lights.

Barak Obama

August 4, 1961

44th President

Dr. Mae Jemisen

In 1992, Dr. Mae Jemison became the first African American woman to go into space aboard the space shuttle Endeavor. During her 8-day mission she worked with U.S. and Japanese researchers, and was a co-investigator on a bone cell experiment.